Very few developments in bourbon over the past several years have elicited such deeply held emotional responses as Diageo’s Orphan Barrel Distilling program. From bourbon bloggers to bourbon drinkers, there doesn’t seem to be anyone familiar with them who doesn’t have some sort of strong emotional reaction either in favor of or against these releases.

Why?

First, let’s review the Orphan Barrel Distilling project.

The OBD project is a product of Diageo. For those unfamiliar, Diageo is the world’s largest spirits company, owning everything from Guinness and Red Stripe Beer labels to Bailey’s, J&B, Smirnoff, Crown Royal and Johnny Walker. They own over 100 different Scotch, Irish, Canadian, and American whiskeys. That makes Diageo a behemoth in the whiskey world…outside of the U.S. Because the main whiskey product of the U.S. is bourbon, and Diageo’s only prior label in the Bourbon industry is Bulleit, which they do not even distill themselves.

The OBD project is a product of Diageo. For those unfamiliar, Diageo is the world’s largest spirits company, owning everything from Guinness and Red Stripe Beer labels to Bailey’s, J&B, Smirnoff, Crown Royal and Johnny Walker. They own over 100 different Scotch, Irish, Canadian, and American whiskeys. That makes Diageo a behemoth in the whiskey world…outside of the U.S. Because the main whiskey product of the U.S. is bourbon, and Diageo’s only prior label in the Bourbon industry is Bulleit, which they do not even distill themselves.

They don’t distill Bulleit, but they do own distilleries. They released plans to build a new Distillery in Shelby County, KY recently where, presumably, they will be making future bottlings of Bulleit. But they also own and have owned many distilleries in the U.S. over the years, they just haven’t actively made bourbon in them. One in particular is the famed Stitzel-Weller distillery in Louisville. Stitzel-Weller was acquired as a side-asset of another acquisition by Diageo in 1992. By then, the facility was aging, and bourbon had not entered into its current boom yet. Diageo ceased production at the facility and let the stills deteriorate. But they kept the many warehouses on the site that were used both for Stitzel-Weller product and by other distilleries (including others acquired by Diageo) as extra warehouse space. With those warehouses, Diageo also got a great deal of whiskey that was aging in them.

With that whiskey was a thus-far unreported number of barrels produced at The Old Bernheim distillery in Louisville, and the successor plant to Stitzel-Weller, the “New” Bernheim facility (now owned by Heaven Hill). These barrels were distilled under the supervision of legendary Master Distiller Ed Foote, who was responsible for what eventually became the holy grail of many bourbon drinkers, Pappy Van Winkle, when he was Master Distiller at Stitzel-Weller, prior to its closure.

The mash bill for these barrels has been reported to be 86% corn, 6% rye, and 8% malted barley. They were made without a purpose in mind. In other words, they sort of just started distilling them without knowing what they would be used for- there were no buyers lined up, and no specific label in mind. So when they were sold with the warehouses, they just sat there.

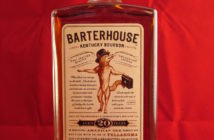

Those barrels make up the Orphan Barrel Distilling program for Diageo, and were released under three labels (with a fourth due to be released in the future): Old Blowhard, Barterhouse, and Rhetoric (The fourth will be called “Strongbox.”) June 2015 Update: Two additional labels have been released: Lost Prophet and Forged Oak.

So what’s the problem here? Why the strong reaction? Really, there are two problems.

The first problem is how Diageo presented the program to consumers. The true story, as outlined in general terms above, is actually pretty interesting from a bourbon fan’s perspective. But that wasn’t enough for Diageo. They presented them as if they were “lost” barrels the distillery had somehow found in the depths of their warehouses and released to a grateful public. They actually tried to pass it off that they weren’t even sure where the barrels came from.

Nothing could be farther from the truth. Companies don’t “lose track” of barrels. They track them meticulously. And the distillery and various other pieces of identifying information are always conveniently stamped on the lid. And Diageo paid taxes to Uncle Sam on each one every year. Diageo didn’t just “find” the barrels, they just “found” the idea to finally bottle them and sell them in the midst of a bourbon boom where demand for unique and aged bourbons is at an all-time high. That would have been fine had they been up front with the public, instead of assuming the bourbon world would take them at face value for such an unbelievable story. In truth, bourbon collectors and drinkers are obsessed with the lineage and histories of the juices they drink. It didn’t take long for bloggers, writers, and historians to poke holes in Diageo’s story. So after a few months, the truth started coming out from Diageo. Well, part of the truth started coming out, because they still won’t release how many of these bottles were actually released (it appears to be a far cry from the “rare” and “extremely limited” descriptors they have thus far reported, as it seems at least 50,000 bottles of Barterhouse alone were released.) That’s a $90 bourbon, by the way. Compare that to the Four Roses 2014 Limited Edition Single Barrel which retailed for between $90 and $100. There were 5,000 bottles of that.

And Diageo refers to OBD as “craft” whiskey. While they are correct in saying there is no definitive definition of “craft” whiskey and they can essentially call anything “craft” whiskey, there can be no doubt that Old Bernheim and New Bernheim did not originally distill these with the idea of small, rare, bottlings in mind. And the word “craft,” in today’s age amidst a craft beer revival where such terms have real meaning, isn’t so ambiguous to the consumer as Diageo would have us believe. They know that. So do we. This is mass distillate in every sense of the word. It’s just old mass distillate.

I’ve also read quite a few criticisms of Diageo’s choice of names and packaging. Many call them “hokie” or “campy” and criticize them for poor name choices. I can’t agree with that. Frankly, I don’t care a whole lot about what name is chosen or what the label looks like anyway, and this criticism just seems to be getting into the realm of petty to me. These are fine to me, and look good on a bourbon shelf. And to be fair, half the bourbon labels out there have gimmicky half-true stories surrounding their creation and heritage already. Diageo is just the latest. Maybe it’s the fact that a traditional Scotch Whisky company is jumping into the Bourbon industry, a traditionally American arena, that sets off so many writers and collectors. If the exact same names, packaging, stories etc. were put out tomorrow by, say, Wild Turkey or Jim Beam, my guess is there would be a lot of rolling of eyes and people saying “there they go again, those scallywags!” with a wink and a smile. But my guess is that the bourbon in the bottles would be much different as well.

So Diageo’s presentation of the OBD has been an issue.

But the second problem is a bit more difficult to solve. The bourbon itself is a problem. It’s certainly not bad bourbon by any stretch. There are some interes ting notes on each, and each release has been a bit different. Old Blowhard is 26 years old, and has almost overwhelming aged oak and wood flavors some have compared to “wet rope.” Barterhouse is 20 years old, and has less overpowering oak, and more of the traditional bourbon sweetness. Rhetoric is a nice blend of the two, is currently at 20 years (and will be released next year at 21 years old, followed by the following at 22 years, etc.) It will be an interesting experiment in the impact of aging on old bourbon. They all clock in right around 90-91 proof. All three of them are fine. But fine is a problem for bourbon ranging from $90 to $150 retail. It’s especially a problem when, in the case of Barterhouse, it’s not even rare.

ting notes on each, and each release has been a bit different. Old Blowhard is 26 years old, and has almost overwhelming aged oak and wood flavors some have compared to “wet rope.” Barterhouse is 20 years old, and has less overpowering oak, and more of the traditional bourbon sweetness. Rhetoric is a nice blend of the two, is currently at 20 years (and will be released next year at 21 years old, followed by the following at 22 years, etc.) It will be an interesting experiment in the impact of aging on old bourbon. They all clock in right around 90-91 proof. All three of them are fine. But fine is a problem for bourbon ranging from $90 to $150 retail. It’s especially a problem when, in the case of Barterhouse, it’s not even rare.

I don’t have inside information on the reason these bourbons weren’t released before today. One can guess there are several. The easiest answer is that Diageo hasn’t been focused on bourbon, and offering a finite-quantity release of bourbon hasn’t really been in their business plan until this recent bourbon boom made it a financial no-doubter to do so. The second reason might very well be that the folks monitoring these barrels never thought they were good enough or ready for release. That’s a slightly scary thought for those dropping 3 figures on a bottle.

Long-aged bourbon is rare these days, but it’s not always better. Many people see 20, 30, even 40 year old scotch whiskeys and assume that older = better for all whiskey. That’s not true with bourbon. Scotch whisky is aged in Scotland, where summers are mild, at best, and winters are cold and windy, but rarely frigid. There just isn’t a huge swing in weather conditions from year to year and season to season. In Kentucky, where most bourbon is aged, winters drop well below freezing for days or weeks at a time, and temperatures reach over 100 degrees in the summer with relatively high humidity. That change of weather accelerates the chemical processes in the barrel. The wood expands and contracts, the whiskey moves in out of the wood regularly, and the aging happens much more quickly than in more consistent climates.

If you consider the makeup of bourbon, or it’s “mash bill,” you will remember that at least 51% must be made up of corn in order for it to be bourbon. Corn, in the short term, is sweet, which is responsible for bourbon’s “Sweet” character compared to other whiskeys. But over time, it becomes a neutral spirit, meaning the flavor of that grain recedes in favor of the barrel flavors and other grains. That’s where the secondary grains come into play. Rye adds spiciness and citrus character, wheat adds velvety sweetness. So in the case of the OBD, we’re talking about very low secondary grain levels. 86% corn and only 6% rye, 8% malted barley (which is primary a texture grain). After 20 or 26 years in the barrel, this whiskey has lost some flavor, and picked up a lot of barrel flavoring. It’s entirely possible that this whiskey is well past its prime, as a higher rye or even wheat level as the secondary grain would stand up better to two+ decades in the barrel. We’re left with a largely corn distillate that has had a lot of time to neutralize over the years. There are quite a few legitimate whiskey reviewers who believe that if these barrels had a prime in which they were full flavored and ready for bottling, they are well past it.

Modern Thirst has yet to publish an official review of any Orphan Barrel offerings. I’ve tried all three to date, and I really want to present the review of all three at the same time, comparing the three of them. But while I’ve tried all three, I don’t have a bottle or sample of Old blowhard on hand to do a proper review, so I’m waiting for the right opportunity.

But based on my initial tastings, I want to reiterate that these aren’t bad bourbons. And it should be noted that  $90 for a 20 year old bourbon isn’t out of line with market prices on other labels. There just aren’t many 20 year old bourbons out there. There are almost none at 26 years of age to compare to. But I’d have a hard time putting these in the same “quality” level as some other 20 year old bourbons I’ve tasted.

$90 for a 20 year old bourbon isn’t out of line with market prices on other labels. There just aren’t many 20 year old bourbons out there. There are almost none at 26 years of age to compare to. But I’d have a hard time putting these in the same “quality” level as some other 20 year old bourbons I’ve tasted.

So keep in mind a lot of the criticism you read on these are based as much on reason #1 (the presentation) as reason #2 (the bourbon.) But some is legit criticism on the bourbon itself as well. If you want to buy a bottle or try it at a bar, do so independent of what all of us bloggers and reviewers tell you. The emotional response on these offerings is so great that it has clouded the perception of a lot of writers. That’s understandable, given their perspective. But it makes it difficult for consumers trying to find input before making a buying choice.

Judge the whiskey based on the whiskey. It’s fine. Is that a $90 or $150 value to you? I can’t make that decision for you. But “fine” is not “exceptional.” Keep that in mind.

For ModernThirst reviews and tasting notes of Orphan Barrel releases, click here.