New to the world of Bourbon and American Whiskey? Looking for some basic info? Here’s a simple Bourbon Primer to get you started.

What is whiskey?

Whiskey is a liquor made from fermented grains.

What is a mash bill?

The mash bill is the recipe, or combination of grains that are mixed and distilled to produce a whiskey.

American Whiskey vs. Others. What’s the difference?

Whiskey was historically made from whichever crops were abundant in the area of the distillery. Hence, most Scotch and Irish whiskys are single malt whiskeys, made up of a single grain. Most American whiskeys are either corn or rye based, since corn and rye are prominent grains in North America. Canadian whiskey is usually a blend of multiple styles, and usually heavy with rye.

Whiskey vs. Whisky. Is there a difference?

Nope. It’s just a spelling choice. Most American distillers use ‘Whiskey” (except Maker’s Mark) while most Scotch distillers use “Whisky.”

Where did the name “bourbon” come from?

The origin of the name is a matter of debate. Some claim it is from Bourbon County, Virginia, which was the large tract of land that was originally part of Virginia, and the section out of which Kentucky was carved. (Kentucky was originally part of Virginia, for those historically-challenged.) Some claim it was from Bourbon Street in New Orleans, where much of it was originally shipped and consumed. Others claim it was from the House of Bourbon, who ruled France and owned the Louisiana Territory which consumed so much of it in the 18th century. Even more will cite Bourbon County, Kentucky (which, ironically, has no active distilleries) as the source of the name. Historians disagree, and it’s not all that relevant anyway. So let’s just accept that it’s called bourbon and move on.

What is bourbon?

Bourbon is whiskey. All bourbon is whiskey. But not all whiskeys are bourbon. Make sense? To put it simpler, bourbon is a kind of whiskey. So what makes a whiskey bourbon? The simple rules that make whiskey bourbon were laid out by Congress, and have been affirmed in various international treaties with most of the United States’ major trading partners.

Congress declared Bourbon to be “America’s Native Spirit” in 1964 and set down some rules.

In order for a whiskey to be bourbon, it must be:

- Made in the United States

- Made from a mixture of grain (mash bill) that is at least 51% corn

- Aged in new, charred-oak barrels

- Distilled to no more than 160 proof (80% ABV)

- Barreled at no more than 125 proof (62.5% ABV)

- Bottled at no less than 80 Proof

To be “Straight Bourbon Whiskey,” it must:

- Have NO added flavoring or coloring

- Be aged at least 2 years

- If it is under 4 years old, the age must be stated on the label.

- If it is aged-stated, the age must reflect the youngest whiskey in the bottle.

Although many people assume the bourbon must be made in Kentucky, that’s not true (see #5 above). To be called “Kentucky Bourbon,” it must be made in the Commonwealth of Kentucky. MOST bourbon is made in Kentucky, but that’s a function of history, passion, and the nifty fact that Central Kentucky sits on a limestone shelf that naturally filters iron (a flavor-enemy of whiskey) out of the ground water, making it an ideal place to make the spirit. We briefly covered the role of Kentucky in bourbon here.

- Typically, the mash bill of bourbon is around 70% or more corn (primary grain), with the remaining portion (Secondary, or flavoring grains) made up of either Rye or Wheat, and Malted Barley

- Corn: Sweet

- Rye: Spicy, Citrus

- Wheat: Creamy, sweet, soft mouth feel

- Barley: Low flavor impact, adds texture and viscosity

Most Bourbon is made from Corn, Rye, and Malted Barley

Traditional (Rye) Bourbons:

High Rye (18%+):

- Old Grand Dad (Jim Beam)

- Basil Hayden (Jim Beam)

- Four Roses (B recipes, including Single Barrel)

- Bulleit

- Old Forester

- Woodford Reserve

- Kentucky Tavern

Standard recipe (<18% Rye):

- Jim Beam

- Bookers, Bakers, Knob Creek, white label, etc.

Booker’s 90/10 - Buffalo Trace

- Buffalo Trace, Eagle Rare, George T. Stagg, Blanton’s, etc

- Heaven Hill

- Elijah Craig, Evan Williams, Henry McKenna

- Barton 1792

- Very Old Barton, 1792 (Ridgemont Reserve), KY Tavern

- Wild Turkey

- 101, Russell’s Reserve, Kentucky Spirit

Typical Wheat Bourbons (“Wheaters”):

- Makers Mark (including Makers 46)

- Larceny

- Old Fitzgerald

- Rebel Yell

- Weller (including Old Weller Antique and William Larue Weller)

- Pappy Van Winkle

Other American Whiskeys:

Wheat Whiskey (at least 51% Wheat):

- Bernheim

- Parker’s Reserve 8th Edition

Rye Whiskey (at least 51% Rye):

- Jim Beam Rye

- Rittenhouse

- Bulleit Rye

- Templeton

- Sazerac

Tennessee Whiskey (Bourbon plus the Lincoln County process, made in TN):

- Jack Daniels

- George Dickel

Bourbon enters the barrel colorless. This freshly distilled alcohol is commonly known as “new make” or “white dog.”

It draws color and flavor from the barrels as it ages.

Why does age affect Bourbon and American Whiskey differently than Scotch Whisky?

- More seasonal variation and extremes in the U.S. vs. Scotland

- New Charred Oak Barrels vs. Used Barrels

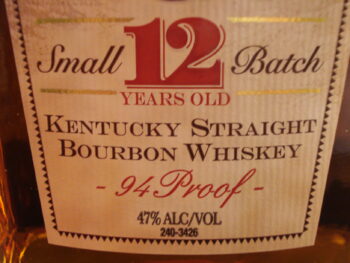

What Does “Small Batch” mean on the bottle? How about “Single Barrel?”

These are actually very common, and very good questions. To answer it, I should first mention briefly how bourbon is aged and bottled. When bourbon is placed into the barrel, the barrel is stored in a large wooden warehouse. The length of time it sits there is up to the distiller depending on the flavors they are going for or the type of bourbon they intend to make. It will be at least 2 years, but it could go as long as 20 to 25 years on very high end bourbon. During that time, the bourbon interacts with the inside of the barrel. The longer they are in the barrel, the more color and flavors they absorb by interacting with the sugars caramelized on the inside of the barrels when they are charred. During this process, there is also a measure of evaporation and oxidation, which actually cause a loss of product in the barrel over time. That amount lost is usually called the “Angel’s Share” in bourbon speak. But those processes are all affected by temperature and time. These warehouses are massive, and very tall. In the hot, humid Kentucky summers, the temperature in the top of these warehouses can vary as much as 30 degrees from the temperatures at the bottom, meaning the barrels within a given warehouse are aging differently depending on where they’re located in the warehouse. To combat this wide variance n flavor, some distillers will rotate their barrels every so often. Barrels at the top will be moved to the middle. Barrels from the middle to the bottom, and from the bottom to the top and so forth. This helps them age similarly. Oftentimes, distillers feel the middle floors produce the best barrels, and some may even have favorite racks on that floor.

But another common process is to mix all the barrels into a “batch.” That way, it all winds up tasting the same, and a consistent product can be sold. A “Small batch” then, is bourbon made from a much smaller batch of carefully selected barrels, usually from each section of a warehouse. There is no hard and fast rule as to what constitutes a small batch, but it can be anywhere from 10 to 25 or even 100 barrels.

But another common process is to mix all the barrels into a “batch.” That way, it all winds up tasting the same, and a consistent product can be sold. A “Small batch” then, is bourbon made from a much smaller batch of carefully selected barrels, usually from each section of a warehouse. There is no hard and fast rule as to what constitutes a small batch, but it can be anywhere from 10 to 25 or even 100 barrels.

A single barrel bourbon, then, means all the bourbon in your bottle comes from the same barrel of bourbon. To keep them somewhat consistent, the distiller will usually take all the barrels from the same section of a warehouse. But a single barrel bourbon often has slightly nuanced differences in flavor from barrel to barrel, making it a more unique experience from bottle to bottle.

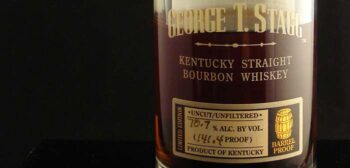

What is barrel proof? How is it different from cask strength?

This is an easy one. When bourbon is removed from the barrel, the distiller often adds water to bring it down to a lower proof (percentage of alcohol) to make it smoother and easier to drink. Barrel proof, which is synonymous with cask strength, means water is not added. The proof of the bourbon as it is removed from the barrel is the proof as it goes into the bottle and is ultimately consumed by you. It’s usually around 60% ABV or higher (120 proof). In other words, it’s a very strong bourbon.

I see a lot of bottles with “Private Barrel,” “Barrel Selection,” or “Private Selection” listed on them. What does that mean?

Now you’re getting into some current trends in the industry. Many distillers have begun private barrel programs. These programs allow a retailer or bar to go to the distillery and select an entire barrel of bourbon to purchase, have bottled, and offer exclusively to their customers.

Now you’re getting into some current trends in the industry. Many distillers have begun private barrel programs. These programs allow a retailer or bar to go to the distillery and select an entire barrel of bourbon to purchase, have bottled, and offer exclusively to their customers.

If you think about how bourbon is made and aged, this is significant in a couple of ways. First, retailers can select the choice barrels, offering bottles to their customers that are slightly varied form the run of them ill production bottles found on shelves. Theoretically, assuming they have a good palette or are guided correctly by the distiller, they can pick the best barrels available to them. A barrel select offering from Four Roses actually won Whiskey of the Year at the World Spirits Competition in San Francisco this year.

That may sound great on its face, but the long-term impact on bourbon for the average consumer may not be as good. There are only so many barrels to go around, and these private selection programs are gaining popularity every day. If all the best are cherry-picked by retailers before the rest are mixed into small batches for standard bottling, will the quality of the bourbon you buy on the shelf suffer in the long-term?

How should you drink bourbon?

Any way you like it.

The long answer for the aspiring bourbon snob is…umm…longer. Because tasting isn’t the same as drinking. The four major facets to look for in a bourbon are the appearance, aroma, taste, and finish. Our guide to bourbon tasting can be found here.

So that’s how you judge and taste a bourbon, but that’s not how you drink it on an everyday basis. For this, I direct you back to the short answer on the last question. Drink it however you like. Don’t let anyone tell you it has to be enjoyed a particular way. Julian Van Winkle, of Pappy Van Winkle fame, says he likes his bourbon on the rocks with a twist of lemon. I originally drank it with ginger ale and a lemon. The ginger ale masks the flavor of the bourbon less than other sodas and mixers, but still cuts the burn a bit. As I got used to it, and craved more bourbon flavor, it became bourbon with just a splash of ginger ale and a lemon. Then I cut out the ginger ale, later the lemon. Now I prefer it neat, chilled, or on the rocks depending on my mood. I rarely mix it.

That’s not an indictment of bourbon cocktails. There are plenty of fine mixed drinks like the Manhattan, Mint Julep, and Old Fashioned that you can proudly order and contain bourbon. But my personal advice is that if mixed is your taste, don’t overspend on the bourbon. The more you add to a bourbon, the less complexity of the spirit you can actually taste. A decent middle-of-the-road bourbon is fine with a soda or in a Manhattan, and pretty much indistinguishable from one made with a $400 bottle of 20 year old top-shelf bourbon.

But if you’re with a group of bourbon snobs, and want to impress them, order your bourbon neat or on the rocks, don’t mix it.

What kind of glass should you use to drink it?

I prefer a Glencairn to drink it neat, but there are multiple other options for drinking it on the rocks, with water, or straight up. See our discussion of different common whiskey glasses here.

So a question I often face is more personal in nature: What kind of bourbons do I prefer?

That’s actually a hard question, because I like a lot of different kinds of bourbons. I like complex bourbons with big flavors. I usually tend towards the higher proof bourbons, 100 proof or above, but I like bourbons down to 90 proof and sometimes even lower, though it needs to be an exceptional bourbon in that instance. The Van Winkle 20 Year Family Reserve is only 90.4 proof, and is a clear favorite, but generally, I prefer bourbons with a rye recipe. The Van Winkle bourbons are “wheated” bourbons, meaning a high portion of their non-corn mash is made up of wheat. There are just so many to choose from, it’s hard to pick a specific brand, style, or type. I’ve always enjoyed Buffalo Trace’s standard bourbons from Recipe #2, like Blanton’s, and the higher proof stuff from Recipe #1 like Col. E. H. Taylor and Stagg Jr. I also love the barrel-forward profiles of Heaven Hill’s offerings such as Elijah Craig.

Obviously, for my personal impressions and official ModernThirst scores of a number of different bourbons, you can always look at our past reviews here.